At the beginning of 2024, I began working on a series I titled Romantic Grotesque, which also falls within my Pop Surrealism practice. The title appeared spontaneously in my mind, as if it wanted to embody the tangle of emotions I wished to express: strangeness and fear, yet also beauty, sweetness, and the allure of the unique. Much like in our everyday lives, I believe beauty never comes in a single form — it always carries a paradox. That is precisely why I felt compelled to create works that are not only admired, but also unsettling; works that urge the viewer to question their own perception of what beauty truly is.

To understand more deeply, we must enter two worlds that may seem opposed: the grotesque and romanticism. The term grotesque comes from the Italian word grottesca, meaning “from the cave.” It first appeared in the 15th century, when archaeologists excavated the ruins of Emperor Nero’s palace in Rome and discovered wall decorations filled with plant motifs intertwined with hybrid creatures—part human, part fantastical—alongside curious little figures. This discovery took place at the end of the Renaissance era, and we can trace how many late Renaissance artists became influenced by these grotesque images. This decorative style later came to be known as the grotesque, and from then on became a widely adopted visual reference throughout the Renaissance. ( smarthistory.org )

Over time, the term grotesque expanded beyond a Roman decorative style to represent what is strange, unusual, or even illogical. In the development of visual art, several Renaissance artists began to adopt the grotesque as a way to portray faces in asymmetrical or caricatural forms. One notable example is Leonardo da Vinci, who created studies of faces with extreme distortions—not merely for comic effect, but also as a form of satire or even symbolic mockery directed at certain characters. ( dailyartmagazine.com )

One of the defining features of grotesque art is its ability to merge—or even collide—two emotional poles: the disgusting, frightening, or absurd on one side, and empathy, irony, or laughter on the other. In general, grotesque works present distorted forms, such as hybrids of humans, animals, or monstrous figures that evoke a sense of strangeness, alienation, and a logic-defying atmosphere. Yet precisely because of this absurdity, they often carry a satirical nuance that provokes reflection. One of the most phenomenal examples of this aesthetic is Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights—a triptych teeming with surreal and fantastical creatures, depicting visions of the world, heaven, and hell, along with the cycles of punishment and pleasure.

The grotesque also emerges as an antithesis to the classical concept of beauty—rational, measured, harmonious, and bound by rigid proportion. In contrast, the grotesque exposes human fragility, odd forms, disharmony, and visual imbalance. The discomfort it evokes is no accident, but deliberately crafted to unsettle—urging the viewer not merely to admire, but to question and contemplate the meaning that lies beneath.

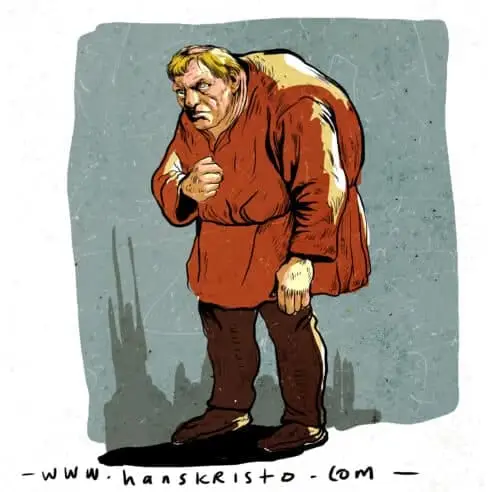

The term romantic grotesque later emerged among critics to describe an artistic direction that not only presents the terrifying and the strange, but also evokes sympathy—both from the artist and the audience. Two seemingly opposing sides—horror and tenderness—are intentionally brought together within the same aesthetic space. In literature, this approach can be seen in the character of Quasimodo, the hunchback from Victor Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris. Though portrayed as deformed and living under the shadow of darkness, Quasimodo radiates a profound humanity that compels the reader to sympathize with him.

Several critics have noted that the era of the romantic grotesque tended to be darker and more serious compared to the medieval grotesque, which was often more comical in tone. In the aftermath of the French Revolution, for example, the grotesque shifted into an expression of fear and alienation—standing in stark contrast to the laughter-laden grotesque of earlier times. One could say that the romantic grotesque revealed the darker side of humanity itself.

In literature, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein illustrates how it is society’s cruelty that gives birth to the monstrous creature. At the same time, the novel reflects society’s fear of its own darkness and solitude. Society becomes the generator of the grotesque through processes of rejection and alienation. In this way, the Romantic era transformed the function of the grotesque: from being mere ornamental strangeness or satirical humor into a tool for evoking empathy and social critique through the tragedy of abnormal figures.

The influence of the grotesque was not limited to architectural ornamentation and Renaissance murals; it also evolved within Baroque, Neo-Classical, and European Romantic art—both in visual and literary forms—as a way to depict the darker dimensions of humanity. Entering the 20th century, particularly in the aftermath of World War I, several art movements emerged as both the excess and the offspring of war. Among them was Dadaism, which rejected traditional artistic rules by deliberately breaking norms and logic. Dada artists, disillusioned by the horrors of war, sought to expose the failure of human reason. In this way, the grotesque re-emerged as a medium of social critique, reflecting on the fractured human condition. Art became a channel to portray the madness of war and the trauma it left behind, while also serving as a psychological escape from collective wounds. Artists increasingly turned to unconventional and diverse media, further expanding the expressive vocabulary of the grotesque. Within this context, the grotesque revealed how humanity could descend into cruelty amid moral collapse, using the metaphor of monsters to voice horror, absurdity, and existential devastation.aa

In the West, the grotesque often appears as though detached from society—more as a symbolic depiction or purely visual expression. In Asia, however, the spirit of the grotesque is embedded in daily life and cultural rituals. In Bali, for instance, terrifying divine figures are not representations of evil, but rather moral reminders and guardians of harmony. Figures such as Barong and Rangda are not seen in black-and-white terms of good or evil; instead, they exist in balance, complementing each other, and playing essential roles in sustaining the equilibrium of life.

I vividly remember my six years of living in Bali. On the eve of Nyepi, the Day of Silence, the community celebrates the ogoh-ogoh festival—a parade filled with monumental, monstrous effigies that are grand, terrifying, and fantastical. Each Banjar (local community) spends weeks preparing their ogoh-ogoh: some appear ferocious, some humorous, and others even touch on erotic or satirical themes. These effigies are paraded through the village before being burned, symbolizing the destruction of the malevolent forces within humanity.

For me, this was not merely an artistic spectacle, but a collective celebration of imagination, spirituality, and the awareness of balance. Perhaps it was precisely from living there that I came to realize: the grotesque is not only a visual style—it is a way for society to understand the paradoxes of life, honestly and ritualistically.

In the past, the grotesque was conveyed in a direct and frontal manner—depicting tragedy, hell, or human sin upon the walls of churches. In the contemporary era, however, its visualization has undergone a significant shift. Today, grotesque imagery often appears in colorful, sweet-looking forms that conceal a bitter undertone. It feels as though irony and fear linger quietly behind the curtain of beauty.

The movement of Pop Surrealism—or Lowbrow Art, which emerged in the United States in the late 1990s—can be seen as a modern recall, or resonance, of the grotesque spirit of the past. Initially, Lowbrow Art leaned heavily on humor and playful absurdity, but over time it evolved into a medium that voiced deeper, more emotional themes—especially within the phase of Pop Surrealism. Both movements, though different in style and context, carry messages about absurdity and inner emptiness that parallel the spirit of earlier grotesque art—only now presented with a different face.

One of the strongest representations of this spirit can be found in the works of Yoshitomo Nara, a Japanese Pop Surrealist and one of the Asian artists I admire most. Nara often portrays paradoxes through childlike figures—innocent in appearance, yet carrying within them a shadowy side of alienation and restrained emotion. His characters frequently appear silent, but within that silence lie sorrow and resistance—not in explosive form, but quietly simmering. He seems to invite us into an inner, solitary space: a soul that never grows old, yet remains wounded and lonely.

Nara’s visual style is deceptively simple, yet within that simplicity lies an expansive field for interpretation. For me, Yoshitomo Nara’s works embody the melancholic dimension of the grotesque, layered with a powerful ambiguity of emotion—a contemporary expression of the romantic grotesque.

Yet what we see in Nara did not emerge out of a vacuum. The traces of grotesque aesthetics can be traced far back, to the works of old masters who, centuries earlier, had already embraced absurdity, distortion, and paradox—albeit with a different visual language.

Francisco Goya

As a court painter of Spain and a witness to history, Goya is often called “the last old master and the first modern artist”. His technical skill was initially shaped by Romanticism, but later underwent a dramatic shift in his series “Los Caprichos” and “Black Paintings.” In these works, he explored the darker sides of humanity, the absurdities of social life, and psychological horrors. For Goya, the grotesque was not merely decorative; it was a form of critique, satire, and even cynicism toward humanity, reflecting the suffering of his age and civilization.

Francis Bacon

Bacon was a phenomenal modern British painter. A figurative artist, he carried the grotesque into the modern era with his signature extreme distortions of the human body, producing visual impressions that were unsettling and terrifying. The figures in his paintings are never pleasing; instead, they disturb the viewer psychologically. His works radiate a sense of screaming—melting forms, alienation, and existential fear.

Salvador Dalí

As a pioneer of Surrealism, Dalí employed the grotesque through fluid forms, twisting bodies, and absurd dreamscapes. For Dalí, the grotesque was a play of imagination that defied logic—opening a window into the subconscious.

Frida Kahlo

Kahlo, whose life was marked by profound suffering, combined self-portraiture with surreal symbolism. Her work transcended autobiography: she painted the trauma of her injured body, emotional pain, and existential struggle. In Kahlo’s paintings, the grotesque appears poetic—sorrow cloaked in romance, bitter reality transformed into poignant beauty.

From these masters, we can see how the traces of the grotesque has continuously transformed, finding new faces in our own time. For me, this represents the most relevant evolution of the grotesque today: imagery that feels familiar, yet provokes unease. Fear is no longer presented directly, but at a distance. As viewers, we are gently led into a meditative space, peeling away layer after layer of aesthetics until we arrive at a reflective moment—realizing that absurdity, inner strangeness, and the failure of logic are inseparable parts of human life.

Pop Surrealism emerges as the language of our age in relation to the works of Bosch, Hugo, or Shelley. It unveils the contemporary veil and serves it on the plate of our daily lives—with visuals that are more accessible, yet no less poignant. It reminds us that the strange, the wounded, and the absurd are not disruptions to beauty—but essential elements of its wholeness and depth

The awareness of the grotesque here does not merely reveal the darker side of humanity, but also invites us to contemplate the absurdity of the world in a reflective way. Rather than sinking into the sweetness of aesthetics or falling asleep within sterile beauty, the grotesque offers a contemplative space—another way of seeing life with honesty and courage.

Click here if you want to Read about the writer | Hans Kristo

Art is not only about what you see on the canvas, but also about the stories and thoughts that linger beyond it. If you’d like to dive deeper into these explorations and stay updated with new works, reflections, and exclusive releases, join my newsletter.