Many people, both casual viewers and devoted art appreciators, often ask: what is Pop Surrealism and where did this art movement actually come from? What we knew first were, of course, two very different currents—Pop Art and Surrealism.

But before going there, I see a recurring phenomenon in the art world: the tension between high art vs low art. This clash is almost inevitable, for the value of art is often bound by exclusivity and commodification. Art is never only expression—it also becomes business.

Some theories believe that there are people with a supposedly “higher” sensitivity and artistic taste than others. The art ecosystem then creates its own structures of validation and hierarchy to decide who is worthy of recognition. Yet once such authority becomes too established, it is almost always questioned—out of that doubt, new antitheses are born.

This tension is also visible in the discourse of high art vs low art, a theme that continues to shape art history and criticism. At certain points in history, low art remained bound to its social function—art that lives in relation to external forces. High art, on the other hand, was positioned as something detached from function, what is often described as “art for art’s sake.”

The most iconic example comes from Marcel Duchamp, who once placed a urinal inside a gallery. What had been a purely functional object was suddenly reframed as art, transformed solely by the context that surrounded it. This gesture was not merely provocation—it questioned, at its core, the very value and boundaries of high art.

But the tension between high art and low art was never limited to the West. In the history of modern art, Western nations often viewed works from outside their sphere as mere “followers.” Modern art was anchored in the West, while other traditions were too often reduced to craft or handiwork—pushed into the margins as low art.

The same tension was also felt in Indonesia. A number of artists and their circles questioned this dominance with a simple yet profound inquiry: is there such a thing as an authentic modern Indonesian art—one not constantly defined or controlled by Western standards and discourse?

Beyond philosophy and theory, the divide between high art vs low art was also tied to the exclusivity of exhibition spaces. Many forms of art dismissed as “low” were denied entry into the major galleries. Among them was the Lowbrow Art Movement.

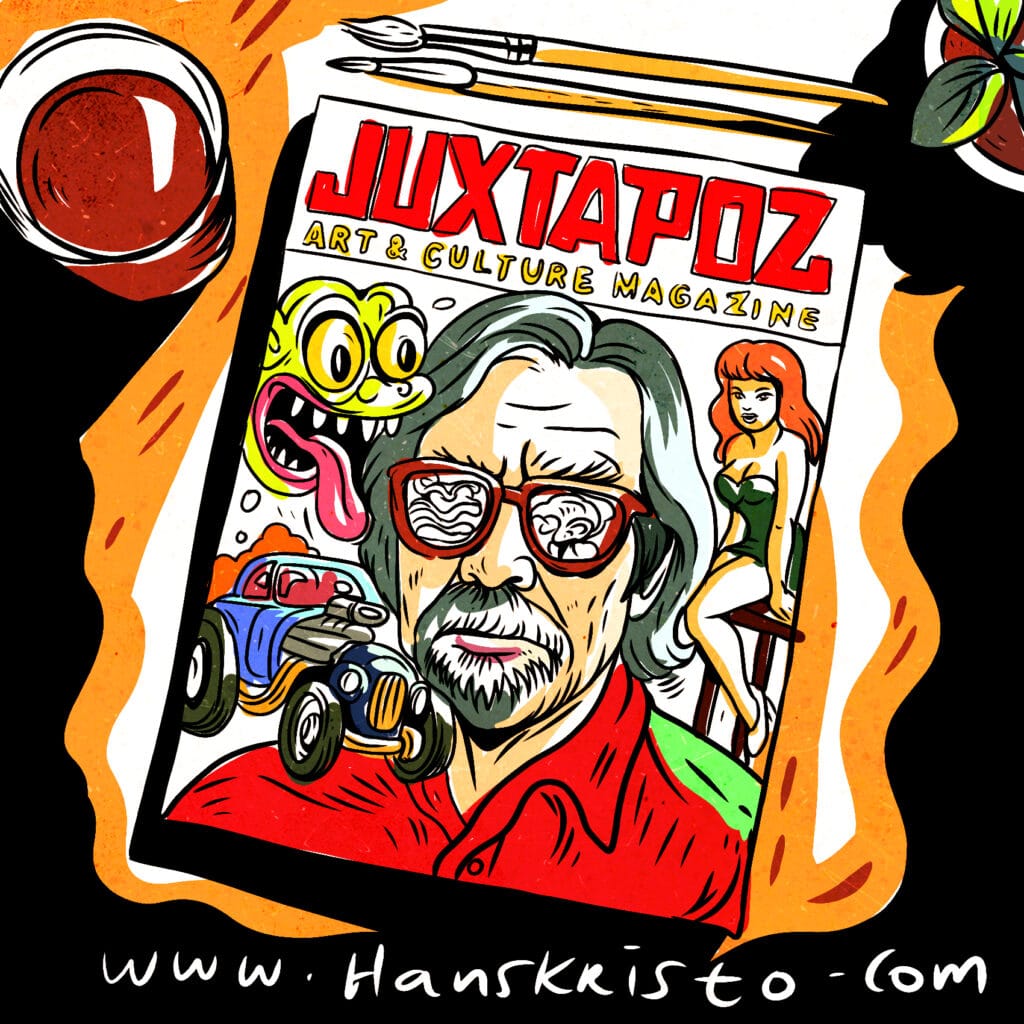

The Lowbrow Art Movement was born in Los Angeles, rooted in surfer culture, hot rod aesthetics, and underground magazines such as Mad Magazine and later Juxtapoz. Its pioneers were not graduates of art academies, but self-taught artists, illustrators, and underground cartoonists.

For years their works were dismissed as kitsch—or even derided as “trash art.” Yet it was precisely from these underground spaces that they built a movement, one that thrived without craving the spotlight of institutions.

Contemporary art and postmodernism, which struck against the grand ideas of modernity—from universalism to absolute truths—opened new possibilities for the democratization of art. Themes once closed off and exclusive began to be questioned, replaced by subjectivity, diversity, and the voices of those who had long been pushed to the margins.

It was within the postmodern space that the Lowbrow Art Movement found the possibility to step out of the underground. Works once dismissed as “trash art” began to enter galleries, slip into the mainstream, and even claim a place within the “major labels” of contemporary art.

One of the central figures in the Lowbrow Art Movement is Robert Williams (Lowbrow artist and Juxtapoz co-founder), as well as the very artist who first coined the term “Lowbrow.” His works often fused sarcastic humor, cartoon characters, and themes unburdened by intellectual pretensions. For this reason, Robert Williams’ Lowbrow art was long regarded as far removed from the world of high art, galleries, or museums of its time.

Over time, lowbrow art grew in popularity. A new generation of artists began to employ more refined and elaborate techniques, even exploring themes of greater depth and seriousness. Gradually, their works caught the eye of major galleries and entered the spaces of the mainstream.

The meeting point between low art and high art became increasingly fluid, giving birth to a new term: Pop Surrealism. This name was chosen to offer a more positive identity than lowbrow—a label that had always carried a tone of dismissal.

Pop Surrealism emerged as a synthesis: it carried the wild, irreverent spirit and sarcastic humor of the Lowbrow Art Movement, merged it with the icons of popular culture—cartoons, skateboards, graffiti—and infused it with the dark, absurd, and uncanny touch of Surrealism. The result was a new visual language: one that stood at once between entertainment and social critique, between fantasy and reality.

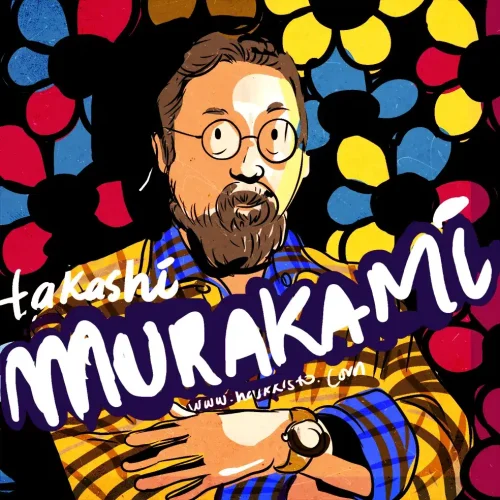

A number of artists soon became recognized as icons of Pop Surrealism. From the United States came Todd Schorr, Mark Ryden, Marion Peck, Jeff Soto, Camille Rose Garcia, Tim Biskup, Gary Baseman, Joe Coleman, and Ron English. From other parts of the world emerged Naoto Hattori, Audrey Kawasaki, Victor Castillo, Alex Gross, Shepard Fairey, Takashi Murakami, Lisa Yuskavage, Josh Agle, Barry McGee, and Gary Taxali.

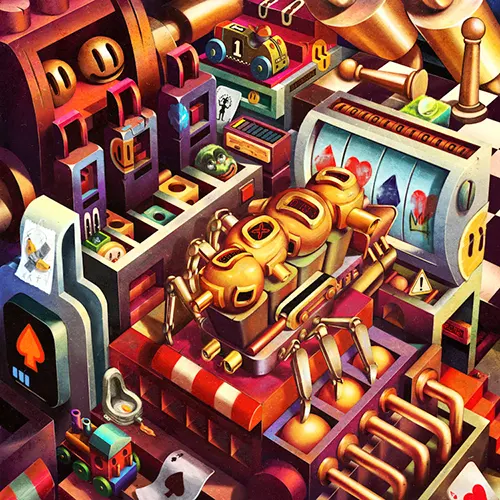

Among the many works of Pop Surrealism, though influenced by the spirit of lowbrow, we can see the movement evolving with its own distinctive style. Most of these works carry narrative messages about everyday human life, expressed through metaphors and popular symbols that feel close to our own experiences.

The thread that unites Pop Surrealism artists is the spirit of preserving diversity, uniqueness, and even strangeness. It is precisely these qualities that allow each work to stand apart, distinct amid the crowd.

From the very beginning of my practice, that tendency has always been present: to dive into metaphors and absurdities. I turned toys into symbols—no longer mere objects, but fragile mirrors of human reality—for often it is play itself that reveals life more truthfully than the players within it.

Amid a world that is crowded and restless, I chose absurdity and silence as my language. I see individuals abandoned once they are no longer “useful,” shadows cast by a culture unflinching in its commodification of human life. In that vision, humanity appears fragile, easily overlooked, and slowly drained of meaning.

These messages continue to dwell within my work—evolving, circling, perhaps even changing form, yet always rooted in absurdity and silence. And perhaps, in the end, the boundaries between Lowbrow Art, Pop Surrealism, and Contemporary Illustration are nothing but illusions. Isn’t that precisely where art finds its life—in the questions that never truly arrive at final answers?

In the end, what unites Pop Surrealism, the Lowbrow Art Movement, and the long-standing debate between high art and low art is not a rigid definition, but the courage to continually challenge boundaries. These movements remind us that art is never still—it flows between galleries and streets, between institutions and underground spaces, between the intellectual and the emotional.

For me, the essence of contemporary illustration lies within this very fluidity. Toys, symbols, fragments of absurdity—they are not mere ornaments, but mirrors reflecting our fragility, our humor, and the strangeness that defines us. Art comes alive not when it offers answers, but when it sustains questions.

Perhaps this is the deepest spirit of Pop Surrealism: a space where contradictions coexist, where beauty and the grotesque overlap, and where silence speaks louder than clarity. Isn’t that precisely where art finds its life—in the questions that never truly come to an end?

Hans Kristo is an Indonesian artist known for blending traditional and digital media. Since beginning his professional career in 2005, he has developed a distinctive style that combines elements of contemporary art, lowbrow, and pop surrealism. His portfolio includes fine art, illustration, and experimental works that bridge high art and underground culture. Explore more of his artworks and projects at Hans Kristo’s official website.