You may have heard the idea that the history of human civilization is essentially a history of change—that the only true certainty in life is change itself. Nothing is ever completely certain except death and change. This statement may sound simple, but from certain perspectives, it does contain truth.

One of the clearest domains that reflects this dynamic of change is the world of knowledge and science. In recent years, it feels as though we are undergoing an epistemic reset. Scientists who once served as references and authorities are beginning to lose their central position—not because their knowledge is no longer relevant, but because new systems of knowledge have emerged, breaking away from the old exclusive paradigms. The internet has opened access that was once limited to academic spaces, dismantling the barriers of exclusivity with surprising ease. It’s no wonder that a number of theories have begun to speak about the ‘death of expertise,’ one of which is discussed by Tom Nichols in his book The Death of Expertise.

In the book, Nichols highlights how the acceleration of the internet brings a double-edged impact: on one hand, it drives the advancement of knowledge, but on the other, it exposes human ignorance even more starkly. The explosion of unverified information is often framed as the democratization of information, even though much of it lacks any methodological foundation. Not to mention the conspiracy theories that circulate freely—often created without scientific grounding and driven purely by sensationalism. Nichols even claims that ‘90 percent of everything on the internet is garbage’—a hyperbole meant to emphasize the overwhelmingly poor quality of information online.

Even worse, such information is often accepted without question. It’s no surprise, because in an age as fast-paced as ours, it has become increasingly difficult to conduct deep verification. Limited time, energy, and resources make the process of filtering information nearly impossible. But what is far more concerning is the dulling of our own critical faculty.

I’ve begun to question just how dependent we’ve become on technology. In the past, before computers and advanced devices existed, we often memorized simple things—like the phone numbers of distant relatives—and it wasn’t difficult at all. Today, doing something like that feels almost absurd. Of course, there’s a positive side: our mental capacity can now be directed toward more substantial matters.

But with the rise of AI, a new question emerges: can we still maintain our critical thinking and cognitive abilities, or will we fall into the trap of technological convenience until our own thinking skills begin to dull?

Human dependence on technology and the accelerating pace of change are deeply interconnected, and neither is easy to separate from the other. Modern civilization offers us little space to pause and reflect on what’s happening; that reflective space seems to have been erased and replaced by slogans like, ‘if you don’t adapt, you’ll be left behind,’ or ‘those who fail to change will be crushed by change itself.’ These statements reveal how the “age” we live in dominates our perception of reality, as if change must always be followed unconditionally.

Then, does holding our ground mean we will be devoured by the times? Is progress always linear, or does it instead open possibilities for other kinds of change shaped by human perspective? In the end, all of these questions can only be answered by time.

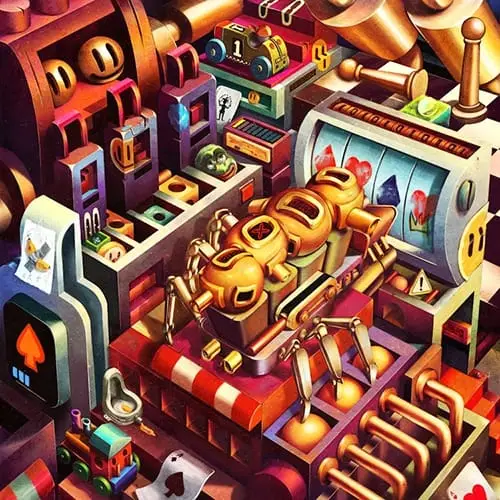

Perhaps these reflections are what led me to contemplate my work In Disruption We Trust. That the only thing humans can truly rely on is change itself. ‘Disruption’ here refers to major shifts or shocks that bring uncertainty and waves of transformation.

In the Homo Ludens collection, humans do not merely play within a system of rules; they are never free from external forces that demand speed, novelty, and unending expectations. Each individual is pushed to constantly produce something new, creating a war of ideas, struggles for influence, and a persistent sense of uncertainty. While such shifts are often imagined as steps toward utopia, they just as easily lead to inequality and dystopia for those who are left behind by the idea of “progress.”

Yet beneath this chaos lies something deeper: the fact that human meaning is never formed in isolation. It is shaped, negotiated, and contested through intersubjective spaces—shared narratives, collective imaginations, and overlapping perspectives that determine what we call truth, value, or even progress. And it is precisely within these intersubjective fields that disruption becomes most visible, revealing not only how we change, but also how we change each other.

Imaginative communities built by humans through fictional narratives may initially provide a comfortable space for their members. However, as time goes on, those narratives can transform into binding rules that trigger conflict. Through this work, I want to illustrate that disruption is something difficult to avoid; it will always come pressing in the end. And humans need to learn not only to accept it, but also to trust the process of change itself.