Today, in the month of December, as Christmas and the New Year 2026 approach, I sit down once again with a cup of coffee and take some time to write a reflection on life and reality. The weather today is neither too cloudy nor too hot. Last month, our city was struck by heavy rainstorms and severe flooding. Several areas and homes were hit by landslides and rising waters; many lives were lost. I heard that nearly 600 victims have been found so far, with houses destroyed and many families separated. I hope the situation can be resolved soon, and beyond that, I hope people can become more aware of their environment: no more littering, illegal logging, or cutting down trees excessively without replanting. All of these actions have devastating effects on the ecosystem.

In moments like these, I am reminded that every era—whether ancient or digital—has its own way of revealing the fragile nature of human existence.

Seeing all of this, I realized that human suffering enters through many doors. Some forms of suffering arrive suddenly through the movements of nature—floods, landslides, or violent winds that strike without warning. But there is another kind of suffering, quieter and slower, one we often fail to notice. A suffering that doesn’t grow from nature, but from the way we live our daily lives.

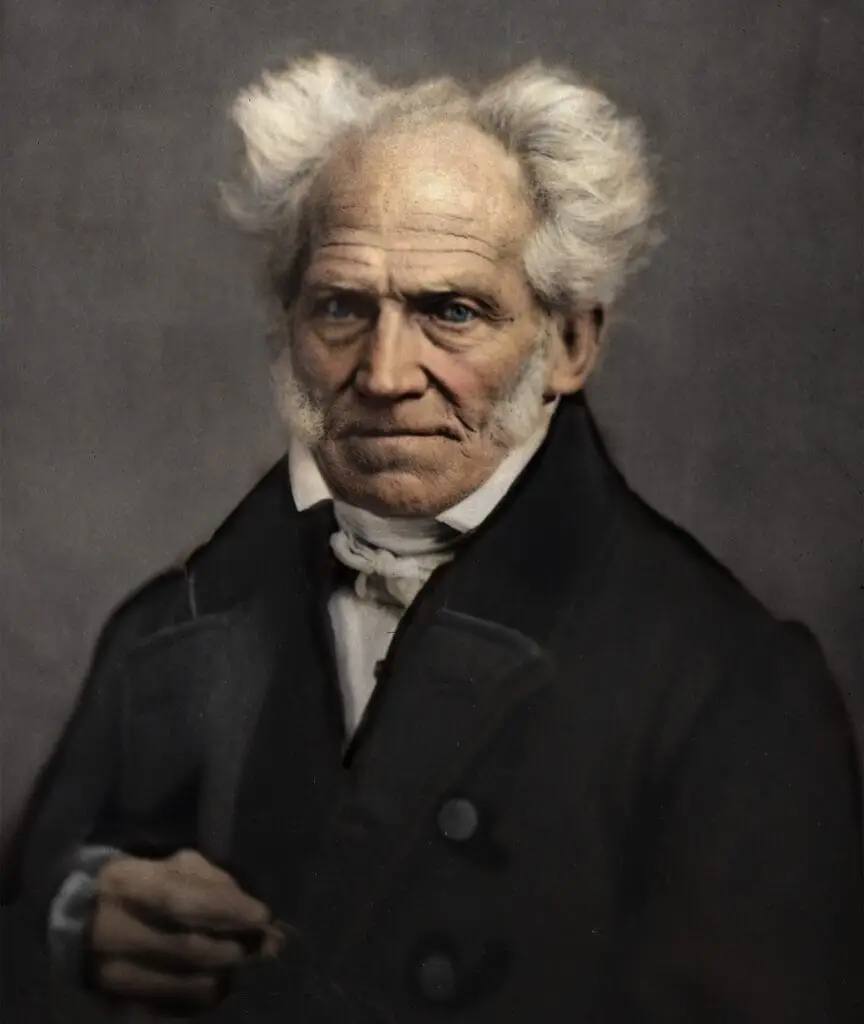

At this point, I am reminded of what Schopenhauer once expressed about the nature of human suffering. Schopenhauer, a 19th-century philosopher known for his bleak yet sharp observations about the human condition, believed that even when the sky is clear, modernity still carries its own storms. He described human beings as creatures driven by the Will—an aimless and irrational desire—that keeps us from ever being truly satisfied. From this, suffering is born, an existential burden that cannot be altered.

If we reflect on modern life, we cannot escape the reality in our hands—the internet. We often become trapped in the impulses of social media: seeking gratification through social validation from the ‘like’ button or comments, while simultaneously comparing ourselves to what appears there—things that are often not real. We scroll endlessly, buy things out of FOMO, and feel pressured to remain constantly productive—all symptoms of desires that multiply faster than we can keep track of. Modern humans easily fall into the cycle of desire; when one desire is fulfilled, we quickly grow bored, then search for a new desire, and repeat the cycle endlessly. This is what Schopenhauer would call illusory desire.

Source: Wikimedia Commons — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arthur_Schopenhauer_1845.jpg (Public Domain)

Schopenhauer said that happiness cannot be attained through the fulfillment of desires, but rather through the reduction of desires. He also emphasized that happiness cannot be found by searching for it outside ourselves, but through reflection and contemplation. One of the genuine escapes from suffering, according to him, is the aesthetic experience of art—an experience that is reflective and contemplative. This idea reminds me of Aristotle’s aesthetic view, which sees the function of art as catharsis, a purification of the soul. In many ways, the two perspectives seem to align.

Unfortunately, modern art no longer follows this path. Art today is often created in shallow, algorithmic, and hyper-accelerated ways, reducing art to mere content. Of course, not all modern art loses its contemplative depth—but the digital ecosystem frequently pushes creators toward speed over substance, making it harder for art to maintain its liberating function. As a result, art’s power to free the soul is diminished, transformed into nothing more than entertainment.

When modern culture promotes multitasking, rejects silence, and fragments our focus, we can see this reflected in the short-form content across the digital world—content that continuously boosts dopamine without giving us space to breathe or reflect. Modern humans also place their expectations on instant results, as an excess of a flexing culture that may not even reflect the truth. We live inside an attention economy designed to keep us stimulated rather than grounded. Schopenhauer offers a more grounded form of happiness through simple living: minimizing desires and understanding ourselves more deeply, allowing us to avoid overthinking, burnout, and depression—the maladies of modern humanity.

For Schopenhauer, life is lived between suffering and boredom. On one hand, suffering arises from desires that remain unfulfilled, and on the other, boredom appears when desires are fulfilled but humans are never satisfied. Therefore, the most reasonable approach is to balance these two states by minimizing desire itself within our minds. For Schopenhauer, human desire and the reality of life are ultimately representations of our inner world.

In essence, for Schopenhauer, life must be grounded in genuine happiness so that we do not become trapped in the Will—an endless, irrational chain of desires that binds us until we lose ourselves. Only through a contemplative spirit and the ability to balance suffering and boredom can we step outside, even momentarily, from this existential structure. Art becomes one of these temporary escapes, and through art we can preserve our empathy, allowing us to feel united with all beings.

In the end, amid the noisy modern world that never stops demanding, perhaps the only breathing space left is the courage to be still—to see life not as a race of desires but as a journey of understanding oneself. This is where art, contemplation, and empathy become the small bridge that saves us from the relentless waves of modernity.

Perhaps today, even for a moment, we can allow ourselves to pause—and listen to the quiet that remains.